Every August, I think of Uyinene Mrwetyana.

Or, rather, I think of what her last day on this earth was like. I imagine a balmy, spring Saturday afternoon, with the world going about its business. I imagine myself, caring for my then-4-month-old daughter and 4-year-old son, in our home, just a short distance away from the site at which Uyinene was killed. I drive past that post office almost daily and the violence that occurred there is never far from my mind when I do. Even when it looks like a regular government building, with people queueing outside it. Even when its doors are closed, like they were that horrible, sunny August day.

But in August, the pretenses stop. The first few years after she was murdered, ribbons and flowers and memorials would appear. Once, I drove past and saw a young couple, probably students, maybe even friends of Uyinene sitting on the steps of the building, in silence, with naked grief on their faces. Another time, someone stuck a huge sign designed to look like a text message that read: Text me when you get home. A reminder so many of us women and girls have intimate knowledge of, writ large and plastered onto the site from which one young woman never returned.

This year, the foundation founded by Uyinene’s family in her memory arranged a walk retracing her final journey from her former residence hall at UCT to the post office. I drove past as they were gathering outside the post office to listen to speakers. The police stood by, as they usually do during marches and public protests. Also standing by – their giant armored truck, reminiscent of those sinister Apartheid-era Casspirs. Maybe because the MEC for Health was there? Or maybe because they were afraid that women would finally, finally try to burn it all down. And who could blame them?

I think of my daughter, 4 months old, just learning this world. I think of someone else’s daughter, headed to the post office on a regular August day. It makes me want to burn it all down, for sure.

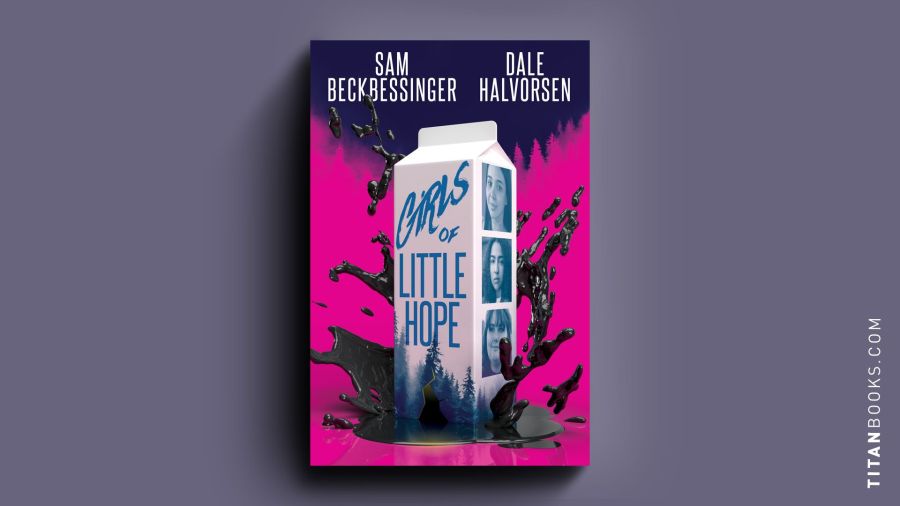

Sam Beckbessinger’s and Dale Halvorson’s sci-fi thriller GIRLS OF LITTLE HOPE explores this notion, amongst others. I wont spoil it for you but the story is a kind of thought-experiment-slash-allegory about a world brought to waste because of the way in which treats women. It is terrifying but also just and justifiable. The conclusion of the story is a strangely happy one, that seems to promise that these girls and these women will finally, finally be left alone.

It’s not such an absurd idea, after all. Girls and women know all too well that the path to self-possession often lies just past the thicket of the patriarchy. What little hope we have of reimagining a world in which girls and women can safely exist lies in obliterating this one.